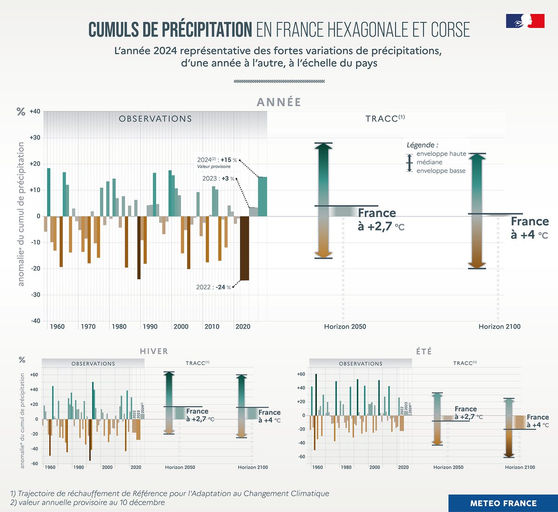

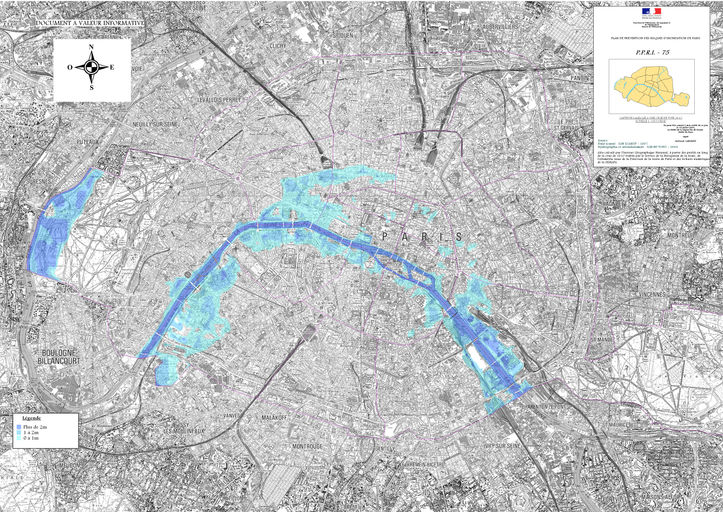

By 2100, France is projected to experience a temperature increase of +4°C. As climate change accelerates, Paris will face more frequent heavy rains, heightening the risk of flooding along the Seine. In fact, the past year was the wettest since 1873. The climate is shifting toward a more tropical scenario, where water not only shapes the urban landscape but also influences human behavior.

This urgent transformation calls for new adaptive strategies, particularly in fundamental aspects of daily life—such as clothing. Designed to respond to local environmental conditions, we believe a new climatic approach demands holistic change, extending beyond architecture and urban planning to fashion and personal attire. Clothing is an integral part of cultural landscapes, reflecting the relationship between humans and their environment.

As Latour suggested, we have to compose, following formulates that are coming from the past, others from the future and other from the presence.

Chaude Couture presents a new vision for rainwear, inspired by tropical climates and cultures where rainy seasons define the rhythm of daily and seasonal life. Moving beyond the plasticization of our bodies and cities, this proposal embraces sustainability, reimagining traditional raincoats crafted from natural materials that have been used for centuries.

PARIS 2100

The year 2024 has been recorded as the wettest in Paris since measurements began in 1873, marking a historic milestone in the city’s climatic history. With a provisional total rainfall of 900.9 millimeters, the French capital narrowly surpassed the previous record of 900.8 millimeters set in 2000, according to data from Météo-France.

Spring 2024 was particularly exceptional, with rainfall reaching 70% above normal levels, accumulating more than 350 millimeters over the season. Autumn also stood out as the wettest since 1986, with record soil moisture levels observed in December, further emphasizing the year’s extreme weather patterns.

With an estimated rainfall anomaly of between +44% and +48% compared to annual averages, Paris exemplifies the broader climatic upheavals affecting the entire country. This record-breaking precipitation underscores the accelerating impact of climate change and confim 2024 as a turning point in the capital’s environmental trajectory.

How should people adapt to the new, wetter climate? How will this affect the behaviour of Parisians?

MADE OF PLASTIC

On rainy days, we are literally covered in plastic. The huge mass of people along the Seine, covered with white plastic raincoat during the wet inaguration of the Paris Olimpic Games is one the last example. Or how thousand plastic bags with legs are crowding and moving in Venice during the raining days rappresents a costume problem of our society.

Plastic production is a major contributor to climate change, as it relies on processes that release significant greenhouse gas emissions. Plastic pollution is a growing environmental crisis, with millions of tonnes of plastic waste entering the oceans, soil and food chain. A study by the University of Newcastle (Australia) found that humans consume about 5 grams of microplastics every week - the equivalent of a credit card! These tiny plastic particles come from water, food and even the air we breathe, raising concerns about their potential health effects.

As plastic production continues to increase, reducing plastic waste and finding sustainable alternatives are key steps to protect the environment and human health.

RAIN DRESS CODE

The use of materials and polymers derived from plastics as a protective clothings has a fairly recent history connected with the de- velopment of chemistry and more modern technologies.

Increasingly waterproof materials to protect the body from the weather have been de- veloped since 1824, with the first jacket pro- duced from rubber. The rain jacket became an essential garment especially in rainy coun- tries. Since that, fashion has developed differ- ent types and shapes.

Can we protect ourselves from the rain without plastic?

TRADITIONAL RAINCOAT

For centuries people have been making natural clothing to protect themselves from the rain.

In East Asian cultures such as Vietnam, China, the Korean Peninsula, and Japan, the use of naturally water-repellent plant fibers, such as rice straw, to create waterproof raincoats and cloaks has been known since ancient times. Raindrops that fell on such garments would run along the fibers and not penetrate into the interior, keeping the wearer dry. They were a common sight among farmers and fishermen on rainy and snowy days, as well as travelers during the rainy season.

In other parts of the world water proof clothes were being made, such in the damp, wet rain forests of South America. Around 1200 AD, Amazonians used the latex like extract from rubber trees to create a primitive waterproofing for their footwear and clothing.

Rain capes made of straw have many indigenous names in Mexico like the well known as capotes de plumas (also chereque, cherépara, or chiripe) in Michoacan, or the capisallo from Tlaxcala so called for the palm leaves’ resemblance to bird feathers.

STRAW

Straw is an agricultural byproduct consisting of the dry stalks of cereal plants after the grain and chaff have been removed. It makes up about half of the yield by weight of cereal crops such as barley, oats, rice, rye, and wheat.

For centuries, straw has served as a valuable building material due to its outstanding physical properties, such as excellent thermal and acoustic insulation, energy efficiency, and low embodied carbon emissions. In particular, rice straw possesses unique characteristics that make it especially promising for sustainable applications. Its naturally water-repellent properties cause water droplets to flow along the length of the fibers rather than soaking through, making it a durable and resilient material.

With climate change reshaping ecosystems, France is likely to see an expansion of wetland areas, leading to increased rice production and, consequently, a greater availability of rice straw.

This shift presents an opportunity to harness straw as a sustainable alternative to plastic, reducing reliance on petroleum-based materials. By repurposing agricultural byproducts like rice straw for other eco-friendly applications, we could take a significant step toward combating plastic pollution while promoting a new way of adaptation to the climate.

CHAUDE COUTURE

The project is balancing art, landscape, and fashion. Chaude Couture embodies a climate- conscious vision—a dialogue between creativity and environmental change, shaped by the reality of increasingly heavy rainfall and its far-reaching consequences. It challenges the way we dress in a shifting climate, transforming garments into protective, architectural forms.

The inspiration comes from ancient raincoats, reimagined and transformed them into micro-architectures. Each piece is more than a garment—it is a shelter, blurring the line between fashion and environment. It is not just about wearing clothing but about wearing the landscape itself, embodying a symbiosis of human, nature, and design.

Chaude Couture comes to life as a collection of unconventional forms crafted from straw—lightweight yet structured—evoking the silhouette of a dome.

A poetic yet functional response to increasingly intense rainfall, it embodies a spontaneous, visionary, and innovative aesthetic that blurs the line between fashion, architecture, and landscape.

For the Biennale d’Architecture et de Paysage d’Île-de-France (BAP!) 2025, the proposal includes the creation of a custom- designed fashion piece crafted from rice straw. This micro-shelter will be producted in collaboration with artisan and it wiill be displayed on a mannequin, symbolizing new possibile way of adaptation to the new climatic scenario.